In the early 19th century, deadly disease outbreaks were common in New York City. Smallpox, yellow fever, measles, and malaria constantly afflicted residents. New York’s access to the Atlantic facilitated the spread of these ailments as sailors and traders brought new strains of infection. Learn more about the most prevalent and deadly of these diseases below on i-queens.

A Part of Everyday Life

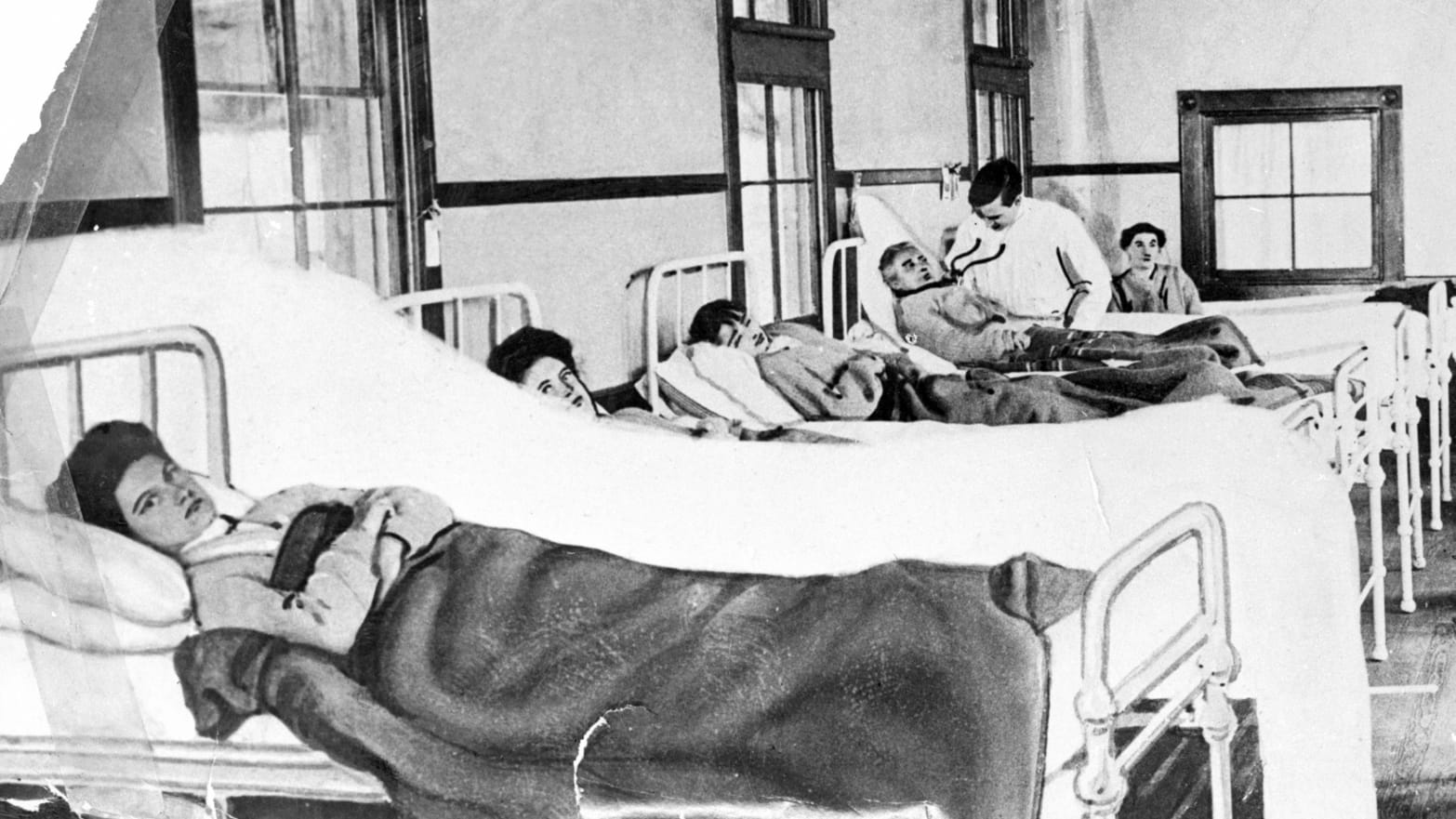

Even in the early 19th century, New York City’s medical professionals struggled to effectively combat outbreaks of infectious diseases. The treatment methods of the time often caused more harm than healing, and the city authorities were reluctant to take responsibility for finding ways to contain or eradicate diseases. The situation was further complicated by poor sanitation.

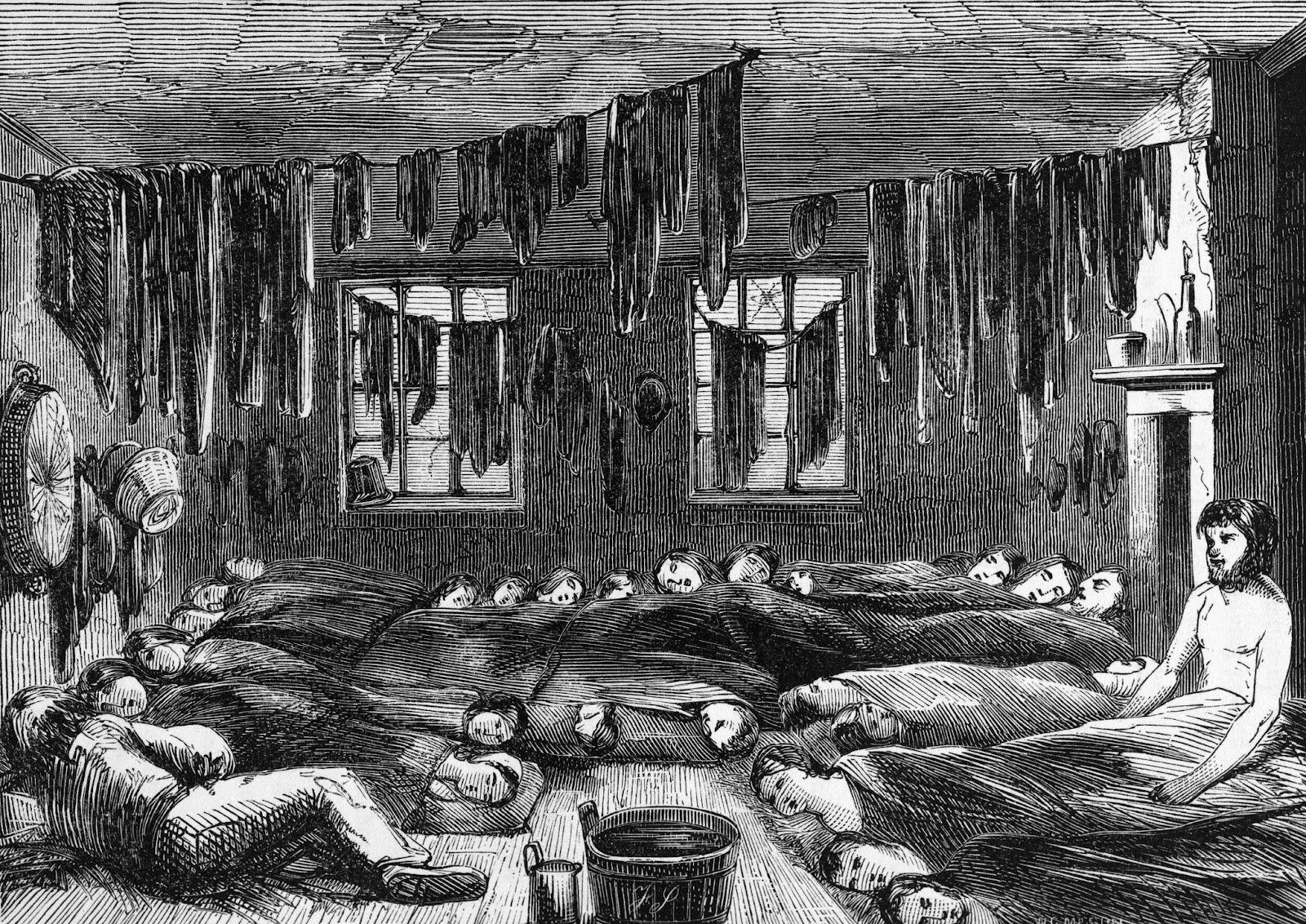

Epidemics became part of everyday life. Diseases spread more rapidly in New York’s poorer neighborhoods, prompting sharp reactions from city leaders. They believed this indicated the moral depravity of the residents in these areas. Poor people were often blamed for their circumstances, leading to insufficient assistance. One of the city’s poorest areas, Manhattan’s Lower East Side, became a breeding ground for diseases.

The Exotic Yellow Fever

The first yellow fever outbreaks in New York were recorded in the 1790s. In 1793, New York’s first Department of Health was established. Ships arriving at New York Harbor from Philadelphia were placed in quarantine, though this measure did little to help.

At the time, the cause of yellow fever was unknown. Many believed it spread through consumption or inhalation of rotten food or coffee vapors. Others thought it had been imported from the Caribbean Islands. The true extent of the outbreak was concealed by the press for fear that people would panic and flee the city.

New Yorkers mistakenly believed the disease was not contagious, and by 1798, it had claimed thousands of lives. The primary response to the epidemic was quarantining infected vessels. Beyond that, the newly formed Department of Health did very little to prevent the spread of the disease.

Yellow fever manifests as jaundice (from which it derives its name) and bleeding. The virus spreads through humans via bites from infected mosquitoes, which themselves contract the virus when feeding on infected monkeys in tropical rainforests. Infected individuals can also infect mosquitoes during the five-day period after symptoms appear. Transmission occurs not only in forested areas with infected insects but also in cities, where mosquitoes spread the virus from person to person. However, the disease does not spread directly from human to human.

Interestingly, in British colonies in America and Africa, yellow fever was often referred to as “Yellow Jack.” Instead of the British Union Jack flag, ships hoisted a yellow quarantine flag to signal the presence of an infected person onboard. Captains were required to inform the port authorities before entering.

The Treacherous Cholera

In 1832, the Department of Health took action in response to a cholera outbreak. The disease reached New York via traders traveling from India to Canada. In just two months, cholera killed more than 3,500 New Yorkers. Ships were once again quarantined, and workers thoroughly cleaned the streets in affected neighborhoods. Several hospitals were opened to assist the sick, with the Lower Manhattan area experiencing particularly high infection rates.

Cholera was especially alarming, as it could kill a person in less than a day. The disease was insidious, as it often lacked specific symptoms and might not manifest initially. Cholera causes such intense diarrhea and vomiting that it can lead to death from dehydration if untreated.

The infection returned in 1849 and persisted until 1854. Overcrowding and poor sanitation in Lower East Side boarding houses and tenement buildings contributed to the disease’s spread, as residents lacked access to clean running water. In 1854, English doctor John Snow discovered that cholera was transmitted through water contaminated by the waste of infected individuals. It is caused by cholera vibrio bacteria, transmitted through the fecal-oral route. After entering the body through the mouth, some bacteria die in the acidic stomach environment, while others reach the small intestine.

In 1842, New York completed the construction of the Croton Aqueduct, a large and complex water distribution system. Five years later, the city banned pig-keeping. This, combined with effective management by the Metropolitan Board of Health, helped reduce cholera outbreaks. The Metropolitan Board of Health, established in 1866, was New York’s first health board and also the first municipal health agency in the United States.

Interestingly, cases of cholera were documented as early as the 9th–7th centuries BCE in Indian Sanskrit writings. One of the first descriptions of the disease dates back to the time of Alexander the Great’s campaigns, as his soldiers likely suffered from cholera. Ancient human cultures in India living near rivers may have facilitated the transition of the infection into a form with clinical symptoms.

With timely treatment, mild cholera results in full recovery. However, without effective therapy, a coma develops within two to three days of infection, followed by death. The disease is worsened by the development of cardiovascular and acute kidney failure.

Another Gastrointestinal Infection

In 1883, a woman named Mary Mallon emigrated to the United States. In 1906, she began working as a cook for a wealthy family on Long Island. Soon after, 11 members of the household developed typhoid fever. The family asked sanitary engineer George Soper to determine the cause of the illness. Soper identified Mallon as the first asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever.

Mary infected everyone she served because she did not wash her hands before handling food. Soper also found that seven of the eight previous households where Mallon had worked had also experienced typhoid outbreaks. The New York City Department of Health placed her in quarantine for three years (1907–1910). Health Commissioner Ernst Lederle released Mary in 1910 on the condition that she would never work in a kitchen again. However, Mallon broke her promise. In 1915, after a typhoid outbreak, she was found working in a maternity hospital on Manhattan under the alias Mary Brown. Consequently, she was confined for the rest of her life on North Brother Island in New York City.As we can see, typhoid fever spreads through contaminated food, water, hands, dishes, linens, and door handles. Flies and cockroaches also play a role in spreading the bacteria on their legs. After entering the body, Salmonella Typhi bacteria multiply and enter the bloodstream. Symptoms of the disease include prolonged fever, fatigue, headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and constipation or diarrhea. Some patients also develop a rash. German bacteriologist and histologist Karl Joseph Eberth discovered the typhoid pathogen in 1880.