Queens is more than just a New York City borough; it’s also a county in New York State. Between 1683 and 1899, the county was twice its current size, extending all the way to Suffolk County. The early history of Queens offers an intriguing look at colonial-era horse racing. Riding competitions have long been a popular sport in the U.S. and worldwide, attracting both betting enthusiasts and spectators eager to watch the riders. Read on for more details on i-queens.

Founder of American Horse Sports

Contrary to popular belief, horses are not native to America. They went extinct shortly after the Ice Age and only returned with the arrival of European colonists in the 16th century. Historians have often debated how Native Americans first acquired horses and how they gained such popularity in North America.

Richard Nicolls, the first English colonial governor of New York Province, facilitated the opening of North America’s first official racetrack in Hempstead Plains, a region in central Long Island. While the Dutch focused on trade and commerce and showed little interest in this sport, the English—especially the military—were passionate about horseback riding. English settlers were active on Long Island, and Nicolls sponsored the first course for horse racing. His project, Newmarket Course in Hempstead, led him to be considered the founder of horse racing in America. He also awarded the first known trophy in the colonies to the winner of the horse race.

Although Nicolls may not have been the most effective colonial governor, his contributions to horse racing were significant. In addition to establishing racecourses, he worked on improving horse breeding techniques, an effort unprecedented in New York.

Decline and Revival

After the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), horse racing experienced a period of decline as racing equipment became scarce and horses vanished. Restoring certain breeds took time, but by the early 19th century, horse breeding had resumed, and American racing regained popularity. Several new racetracks opened on Long Island.

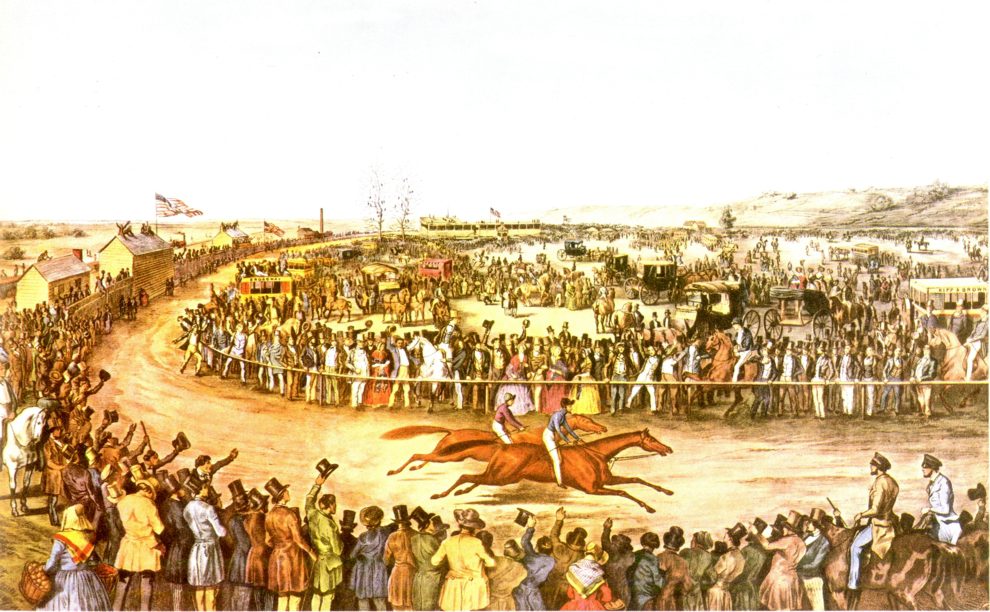

In the early 1800s, new tracks were developed in the county, including Union Course, Fashion, and Centerville Course near the present-day neighborhood of Corona, as well as National Course near LaGuardia Airport. Union Course became the key racing venue with its dirt tracks, though spectators initially watched from their vehicles due to the lack of grandstands.

In 1823, Union Course hosted the famed North-South rivalry races. The champion horse Eclipse—descendant of Messenger, a famous thoroughbred brought to the U.S. after the American Revolution—took victory. Messenger himself, while lacking a long racing career, sired many racehorses of the 20th century. Known for his large, expressive ears, broad, bony head, prominent Roman nose, and robust limbs, Messenger’s impressive height (160 cm) and striking build drew attention.

As racing gained popularity, racetracks evolved. Luxurious grandstands emerged, professional management became the norm, and betting practices changed.

The Legendary Aqueduct

On September 27, 1894, Aqueduct Racetrack opened in Queens on the site of a former Brooklyn water supply plant. By the mid-20th century, this facility was recognized as the most modern horse racing complex in North America, with a seating capacity of over 40,000. In 1975, a winter dirt track was installed indoors, allowing Aqueduct to operate year-round. In October 1981, it welcomed one of New York City’s largest restaurants, Equestris.

In 2011, the first and second levels of Aqueduct’s grandstands were transformed into the multi-level Resorts World New York City Casino. With over 6,500 games and numerous fine dining options, this casino attracts over 10 million visitors annually.

Aqueduct hosts thoroughbred horse races from late October through early April, including the Wood Memorial Stakes in April—a preparatory event for the Kentucky Derby. Aqueduct is part of the New York Racing Association, a nonprofit organization managing New York State’s three largest thoroughbred racetracks.

Notably, the racetrack has its own four-track New York City subway station, accessible to people with disabilities and operating 24/7.

“The Sport of Kings”

Horseback riding is a popular pastime among the elite and is known for its exclusivity and high costs. With New York State’s long-standing history of horse racing, it’s no wonder that the “sport of kings” remains exceptionally popular here.

The art of equestrianism began during the Hellenistic “Golden Age,” evolved with Roman riders, and spread with horse breeding across Europe. Horses were first domesticated in Scandinavia, Iran, and Central Asia around the 4th–3rd centuries B.C.

The first documentation of horses used in war, games, and parades came from the Greek historian Xenophon around 370 B.C. Romans quickly adopted Greek traditions, using horses for warfare, sports, and entertainment. From the 9th–12th centuries, innovations like harnesses, saddles, and stirrups further developed riding in Western Europe. Between the 9th and 15th centuries, the institution of knighthood spread throughout Europe, gaining prominence during the Crusades as knights’ armor and horse gear evolved to offer better protection.

Horses first arrived in America in 1493 and 1518, aboard the caravels and galleons of Christopher Columbus and Hernán Cortés. Native Americans cared for the horses, enabling their spread across the land. From the late 17th to early 18th century, Native American tribes acquired horses through trade, theft, or capture, becoming the proud owners of many steeds.

They domesticated the semi-wild horse of the American plains—the mustang. In Spanish, the term “mustang” translates to “without an owner,” making the mustang a symbol of freedom for many Americans. Nomadic Plains Indians used mustangs for bison hunting, transporting goods, trade, and warfare.

Mustangs usually form small herds composed of either a stallion with a harem of 2–18 mares or groups of young horses or bachelors. Interestingly, some Native Americans believed that mustangs with spots on their heads had magical properties. These “mascot” horses were thought to guarantee victory in battle.