Eugenie Clark, known as the Shark Lady, was an American ichthyologist who performed multiple underwater dives to study venomous fish and shark behavior in tropical waters. She was one of the few people who explored marine life in this way. Clark transformed the scientific beliefs concerning sharks, making numerous important discoveries for understanding fish biology. Learn more about the pioneer of scuba diving, who did it for research purposes, at i-queens.

Early years

Eugenie Clark was born May 4, 1922, in New York City. She was raised in Queens and attended school here. She was the only Japanese-born student at her school. Her father who was American died when the girl was two years old, leaving her mother to raise the child on her own.

Clark was interested in marine science from an early age, and many of her school reports focused on marine biology. Eugenie grew up spending her weekends at an aquarium. When the girl was about nine years old, her mother took her there before heading to work at a newsstand. Clark liked everything about the ocean and aspired to swim with sharks in glass tanks one day. The work of American naturalist William Beebe fueled her interest in this subject.

Wandering around the aquarium, Clark had no idea that she would spend most of her life underwater, exploring the depths of the Red Sea and coming face to face with the “gangsters of the deep,” as she referred to sharks.

The beginning of scientific activity

Eugenie’s youthful curiosity led to a successful career. She graduated from Hunter College with a Bachelor of Arts in zoology, while also studying at the University of Michigan Biological Station during summer. For a while, Clark worked as a chemist for the Celanese Corporation, a technology and specialty materials company.

Eugenie’s application to Columbia University’s graduate school was turned down owing to concerns that she would abandon science for the sake of family. Ambitious Clark, on the other hand, obtained a master’s degree in arts and a doctorate in zoology from New York University. During her graduate studies, Clark conducted research in various institutes, museums and laboratories.

From 1946 to 1947, she worked as a research associate at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California. There, the woman learned to dive using technology that preceded the autonomous underwater breathing device, now known as aqualung.

In 1947, an ichthyologist was assigned to study marine life in the Philippines, but the FBI detained her owing to concerns about the scientist’s Japanese origin. This was because the Japanese occupied the Philippines during World War II. A mere ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was occupied by the Empire of Japan. Ultimately, Clark was denied permission to explore the Philippine seas.

In 1949, the scientist conducted research on the fish population in Micronesia. After receiving a scholarship, Clark carried out more research in the Egyptian city of Hurghada and along the relatively unexplored northern Red Sea coast.

In the sea, she discovered the fish Pardachirus marmoratus, which can emit repellant, a substance that repels sharks. In addition to making hungry sharks stop, these fish cause sharks to shake their heads from side to side. Clark investigated the repellent’s possible usage for humans but discovered that it would not be effective enough to be employed in items such as sunscreen.

The reports, in which Eugenie described her experience in the Red Sea, captivated audiences of all ages. People packed conference rooms to hear stories about the unique inhabitants of the seabed. Clark described her exploration of the Red Sea in her book “Lady with a Spear”.

Working at the laboratory

In 1954, a couple of entrepreneurs and philanthropists, Anne and William H. Vanderbilt, invited Clark to speak at a public school in Englewood, Florida. They were so pleased with her performance that they decided to build an ichthyology laboratory in Florida called the Cape Haze Laboratory. Its goal is to develop marine science and education while also promoting the conservation and sustainable use of marine resources. For the general audience, their research is interpreted through the public aquarium and educational laboratory program.

Clark worked at the Cape Haze Laboratory alongside Beryl Chadwick, an experienced fisherman. Researchers from all around the world came to study at Cape Haze, where the research station was located.

In the year the lab was built, a cancer researcher asked Clark to capture several sharks to study their livers, which led to the creation of a live shark tank on the premises. In 1958, Clark trained Atlantic lemon sharks and other species to push a target to get food. This study contradicted long-held beliefs that sharks lack intelligence. Following that, Clark became an advocate for shark conservation and worked to dispel public fear of animals. Eugenie devoted much of her time to repairing the predators’ bad reputation. She conducted public lectures and even rode the back of a 50-foot whale shark!

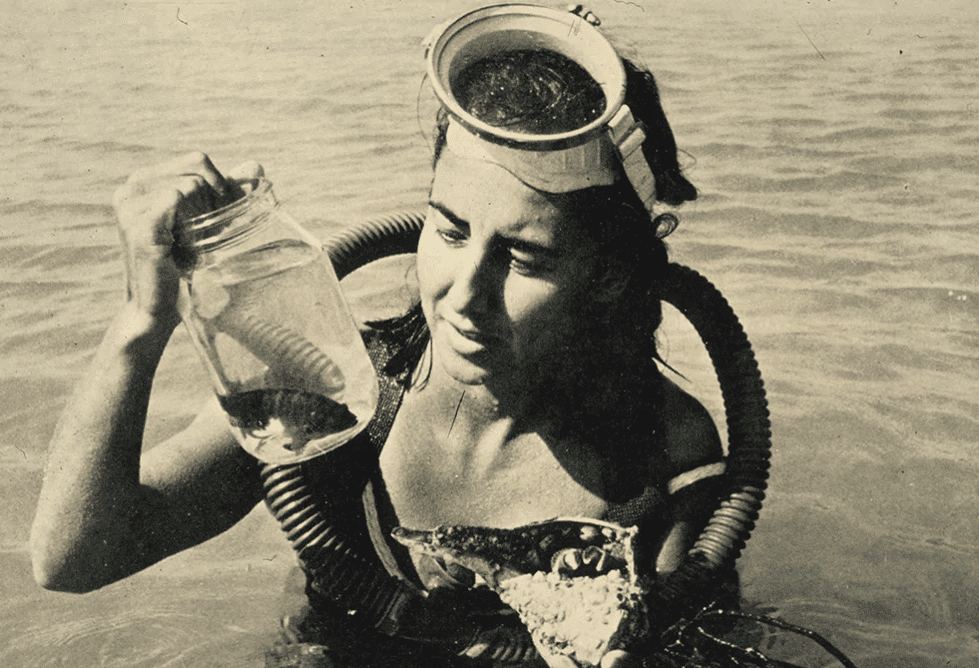

Clark performed multiple behavioral, reproductive and anatomical research on fish. She frequently scuba-dived in local waters, capturing species in glass jars and transporting unknown samples to the laboratory for further research.

In 1960, the laboratory relocated to Siesta Key, Florida. Two years later, the researcher participated in a study of the southern Red Sea. She then studied not only sharks but also other fish, particularly pelagic species (capelin, herring, sprat, mackerel, etc.).

In 1966, Clark left the lab in favor of teaching. In 1973, she visited caves in Mexico where sharks were reported to be motionless and unresponsive. She theorized that freshwater springs in caves help fish expel parasites, which are facilitated by the discovery of parasite-eating remora fish in caves.

In 2000, Eugenie returned to the Cape Haze Laboratory, which by that time had changed its name to Mote Marine Laboratory. The woman worked there till she passed away. The scientist died of lung cancer in 2015 at the age of 92, leaving a remarkable legacy as an ichthyologist, founder of a scientific discovery institute and a pioneer for women in science.

Main accomplishments

Throughout her career, Eugenie Clark:

- discovered that some sharks do not need to swim constantly to breathe. Her discovery of sharks in a state of sleep has greatly contributed to the understanding of their biology.

- was the first to utilize operant conditioning to train sharks to click on targets and execute other tasks. This revolutionary method of training mammals had previously been used for dogs and dolphins, but not for fish.

- was the first scientist in the US to artificially fertilize fish.

- dispelled numerous myths and misconceptions about sharks. The ichthyologist’s efforts have altered the public perception, resulting in significant conservation efforts for these animals.