Due to its large size, New York City was the first American city to face health problems associated with rapid urbanization. By the late 19th century, densely populated areas of New York were overflowing with tenement buildings. One of the poorest neighborhoods, Manhattan’s Lower East Side, became a breeding ground for disease. Poor people were often blamed for their misfortunes, resulting in inadequate support. Many similar neighborhoods also existed in Queens. Learn more about the development of the healthcare system in Queens below on i-queens.

Early Institutions

In the 1790s, New York recorded its first yellow fever outbreaks, leading to the creation of a voluntary public health committee. The next step was the establishment of the Board of Health in 1796, a government agency that implemented quarantine measures. Over the next 60 years, temporary health commissions were periodically established to combat epidemics. As diseases were primarily caused by poor sanitation, these commissions initiated city cleanups.

In the mid-19th century, a significant influx of Irish and German immigrants further worsened the city’s sanitary conditions, increasing mortality rates. The first public health board in New York was established in 1866—the Metropolitan Board of Health—the first municipal health agency in the U.S. Since its creation, this board has looked after the health of all New Yorkers.

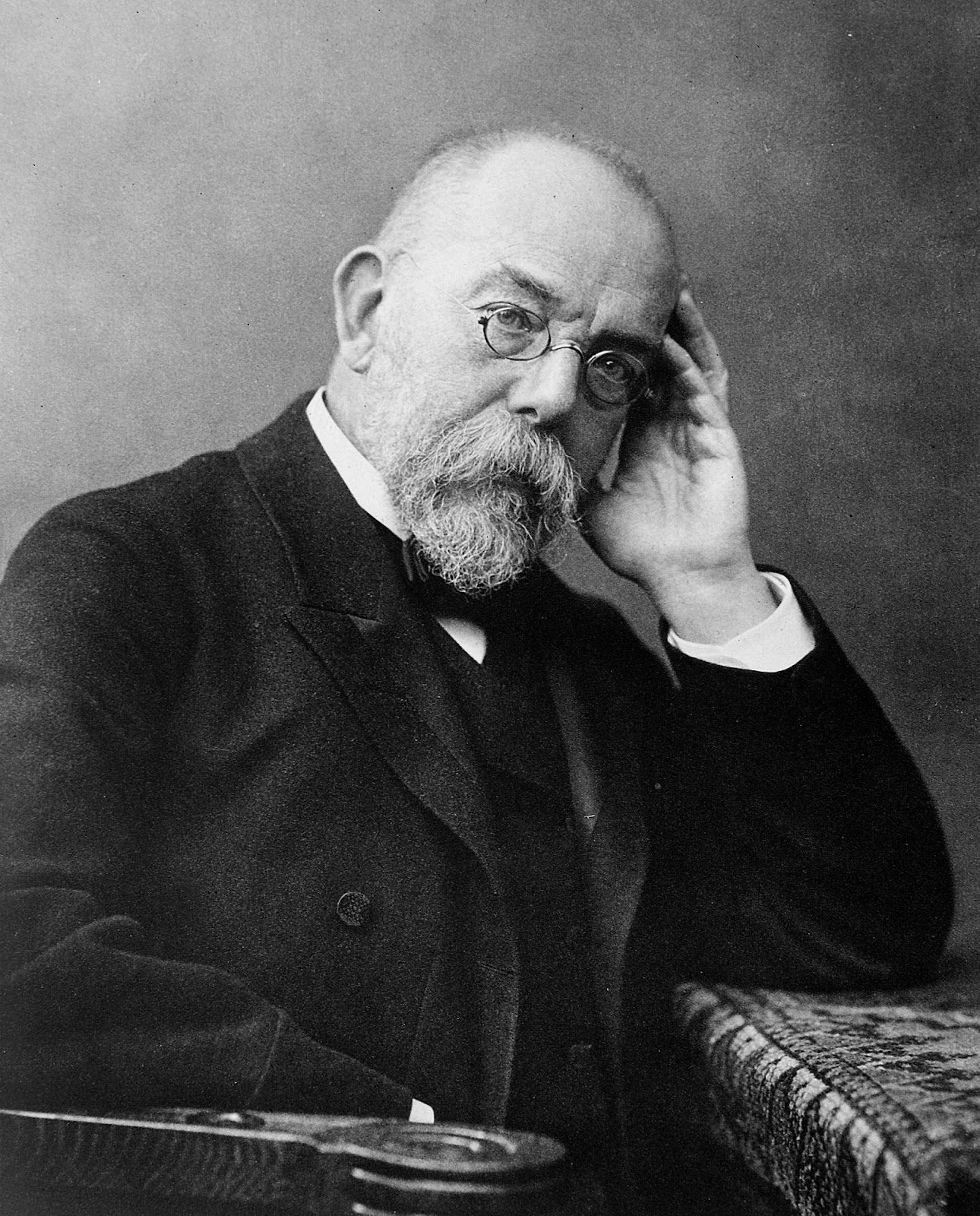

For much of its history, public health in New York, as in other cities, focused on waste, sewage, and epidemic disease control. The bacteriological revolution of the late 19th century radically changed this approach. German microbiologist Robert Koch discovered the pathogens responsible for tuberculosis, cholera, and anthrax, sparking a microbiological revolution, though at the cost of human lives. Koch experimented with medications on residents of African colonies.

System Consolidation

In 1898, New York City underwent consolidation, making Queens one of its five boroughs. This resulted in the unification of many small, inefficient health boards into a single municipal system, subjecting Queens and other borough residents to strict city health regulations.

Newtown Creek, an East River tributary along the Queens-Brooklyn border, frequently became a disease hub, as industrial waste and Brooklyn sewage flowed into it. Neither Queens nor Brooklyn authorities, nor the State Health Board, wanted to take responsibility for cleaning it, leading to progressively worse pollution. Eventually, hydrogen sulfide levels were so high that white buildings turned black. In 1896, the state passed a law requiring an adequate sewage system in Brooklyn, sparking efforts to clean up the creek.

Each of the five boroughs had an assistant registrar to gather vital statistics on residents. This task was challenging in the ethnically diverse Queens, where some dismissed former health workers continued issuing burial permits long after being dismissed.

In the early 20th century, smallpox and malaria cases spiked. Malaria was especially prevalent in Queens, Richmond, and the Bronx. New rules required medical facilities to report all cases. Interestingly, in the 1910s, Richmond and Queens still lacked facilities for infectious disease patients.

The War Period

The United States attempted to maintain neutrality but officially entered World War I in April 1917 as an ally of the Entente. The American army was most active on the Western Front in Europe from October 1917 until the war’s end on November 11, 1918.

The healthcare system was impacted as many New York nurses and doctors were deployed to military medical service, leading to a shortage of qualified workers in the city. Food demand rose, prompting the Food and Drug Bureau to conserve food while being less stringent on quality. Troop movements spread diseases, and military camps added to the workload for the Department of Health, worsened by the 1918 influenza epidemic.

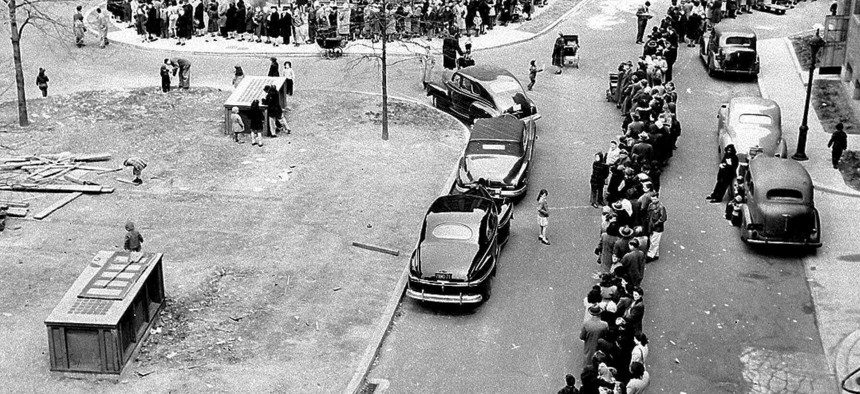

The U.S. entered World War II on December 7, 1941, fighting again on the Western Front. The war brought further changes to the Department of Health, which had to take on new responsibilities amid severe labor shortages.

At the end of 1941, nurses were trained to work as assistants, and the Bureau of Nurses provided instructions on handling chemical weapons. As a precaution, some nurses also completed Red Cross courses.

The Department of Health managed fuel and food supplies. To reduce fuel shortages, minimum temperatures in apartments and residences were lowered from 68ºF to 65ºF. Fears of gas attacks led bureau employees to learn decontamination methods for food affected by poisonous gases.

To increase available food, Health Department inspectors lowered the previously high meat production standards. Despite this, shortages occurred, prompting the city to open several horse meat stores.

The waters of Newtown Creek were still polluted, leading to the cancellation of all well water permits. Before obtaining new permits, each well and water network had to pass a thorough inspection. This, along with regular chlorination of water from reservoirs in upstate New York and the city, helped slow the spread of E. coli.

Active Development

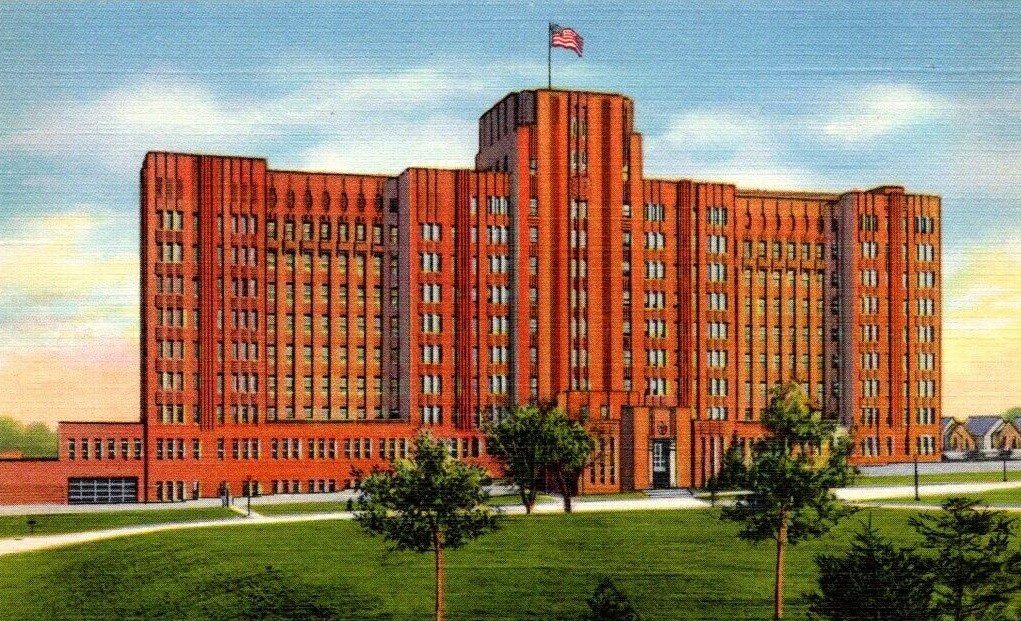

In 1935, Queens General Hospital, the first municipal general hospital in Queens, opened its doors, admitting its first patient in November of that year. The hospital served those who could not afford private care.

In May 1960, Queens and Brooklyn launched a mass glaucoma screening program for the elderly. Around 50 ophthalmologists opened 12 testing centers in their offices, followed by the opening of three permanent glaucoma treatment centers in these boroughs. Additionally, the cancer and diabetes detection services expanded, with cancer clinics screening for cervical cancer, lung cancer, and upper gastrointestinal tract cancer.

The Queensbridge Health Maintenance Program successfully integrated medical, social, and housing services for the elderly, with a special focus on maternal and child health. Prenatal care improved, a comprehensive children’s vaccine was developed, and family healthcare became more accessible. By 1918, the Bureau of Child Hygiene maintained nine eye clinics, one of which was in Queens. Since then, new hospitals, clinics, and healthcare facilities have continued to emerge in the borough and the city as a whole.